Lecture 16

DANL 100: Programming for Data Analytics

Byeong-Hak Choe

October 25, 2022

Exam Policies

During the exam, ...

- Students can read any books, paper sheets, PDF files on PDF reader apps, Python Scripts or text files on Spyder.

- Students are not allowed to use other apps, for example, Google Docs, Google Sheets, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, Microsoft PowerPoint, Numbers, Pages, Keynotes, Notes.

- Students can visit (1) the class website (https://bcdanl.github.io) and (2) the Canvas website for the course.

- Students are not allowed to visit any other websites, such as Google, Stack Overflow, and Gmail.

- Students can communicate with Byeong-Hak Choe.

- Students are not allowed to communicate with other students.

Functions

Functions

- So far, all of our Python code examples have been little fragments.

- These are good for small tasks, but no one wants to retype fragments all the time.

- We need some way of organizing larger code into manageable pieces.

- The first step to code reuse is the function: a named piece of code, separate from all others.

- A function can take any number and type of input parameters and return any number and type of output results.

- We can do two things with a function:

- Define it, with zero or more parameters

- Call it, and get zero or more results

Functions

Define a Function with def

To define a Python function, we type

def, the function name, parentheses enclosing any input parameters to the function, and then finally, a colon (:).Function names have the same rules as variable names (they must start with a letter or

_and contain only letters, numbers, or_).

- Let's define a very simple function that has no parameters.

def do_nothing(): pass # indention is needed here- We use the

passstatement when we want Python to do nothing.- It's the equivalent of This page intentionally left blank.

- We call the

do_nothing()function just by typing its name and parentheses.

do_nothing()Functions

Call a Function with Parentheses

- Let's define and call another function that has no parameters but prints a single word:

def make_a_sound(): print('quack') make_a_sound()- When we called this function, Python ran the code inside its definition.

- In this case, it printed a single word and returned to the main program.

- Let's try a function that has no parameters but returns a value:

def agree(): return True- We can call the

agree()function and test its returned value by usingif:

if agree(): print('Splendid!')else: print('That was unexpected.')Functions

Arguments and Parameters

- Let's define the function

echo()with one parameter calledanything.- It uses the

returnstatement to send the value of anything back to its caller twice, with a space between:

- It uses the

def echo(anything): return anything + ' ' + anythingecho('Geneseo')The values we pass into the function when we call it are known as arguments.

When we call a function with arguments, the values of those arguments are copied to their corresponding parameters inside the function.

Functions

Arguments and Parameters

def echo(anything): return anything + ' ' + anythingecho('Geneseo')The function

echo()was called with the argument string'Geneseo'.- The value

'Geneseo'was copied withinecho()to the parameteranything, and then returned (in this case doubled, with a space) to the caller.

- The value

Functions

Arguments and Parameters

- Let's write a function that takes an input argument and actually does something with it.

- Call it

commentary, have it take an input string parameter calledcolor, and make it return the string description to its caller:

- Call it

def commentary(color): if color == 'red': return "It's a tomato." elif color == "green": return "It's a green pepper." elif color == 'bee purple': return "I don't know what it is, but only bees can see it." else: return "I've never heard of the color " + color + "."Functions

Arguments and Parameters

- Call the function

commentary()with the string argument'blue'.

comment = commentary('blue')- The function does the following:

- Assigns the value

'blue'to the function's internal color parameter - Runs through the

if-elif-elselogic chain - Returns a string

- Assigns the value

- The caller then assigns the string to the variable

comment.

- What did we get back?

print(comment)A function can take any number of input arguments (including zero) of any type.

It can return any number of output results (also including zero) of any type.

- If a function doesn't call

returnexplicitly, the caller gets the resultNone.

def do_nothing(): passprint(do_nothing())Functions

None Is Useful

Noneis a special Python value that holds a place when there is nothing to say.- It is not the same as the boolean value

False, although it looks false when evaluated as a boolean.

- It is not the same as the boolean value

thing = Noneif thing: print("It's some thing")else: print("It's no thing")- To distinguish

Nonefrom a booleanFalsevalue, use Python'sisoperator:

thing = Noneif thing is None: print("It's some thing")else: print("It's no thing")- Zero-valued numbers, empty strings (

''), lists ([]), tuples ((,)), dictionaries ({}), and sets (set()) are allFalse, but are not the same asNone.

==is for value equality. It tests if two objects have the same value.isis for reference equality. It tests if two objects refer to the same object, i.e if they're identical.

a = [1, 2]b = ac = a[:]a == b # True or False?a == c # True or False?a is b # True or False?a is c # True or False?- Let's write a quick function that prints whether its argument is

None,True, orFalse:

def whatis(thing): if thing is None: print(thing, "is None") elif thing: print(thing, "is True") else: print(thing, "is False")- Let's run some sanity tests:

whatis(None)whatis(True)whatis(False)- How about some real values?

whatis(0)whatis(0.0)whatis('')whatis("")whatis('''''')whatis(())whatis([])whatis({})whatis(set())- How about some real values?

whatis(0.00001)whatis([0])whatis([''])whatis(' ')Functions

Positional Arguments

The most familiar types of arguments are positional arguments, whose values are copied to their corresponding parameters in order.

This function builds a dictionary from its positional input arguments and returns it:

def menu(wine, entree, dessert): return {'wine': wine, 'entree': entree, 'dessert': dessert}menu('chardonnay', 'chicken', 'cake')Positional Arguments

- A downside of positional arguments is that we need to remember the meaning of each position.

menu('beef', 'bagel', 'bordeaux')Keyword Arguments

- To avoid positional argument confusion, we can specify arguments by the names of their corresponding parameters, even in a different order from their definition in the function:

menu(entree='beef', dessert='bagel', wine='bordeaux')# Specify the wine first, but use keyword arguments for the entree and dessert:menu('frontenac', dessert='flan', entree='fish')- If we call a function with both positional and keyword arguments, the positional arguments need to come first.

Functions

Specify Default Parameter Values

- We can specify default values for parameters.

- The default is used if the caller does not provide a corresponding argument.

- Try calling

menu()without thedessertargument:

def menu(wine, entree, dessert='pudding'): return {'wine': wine, 'entree': entree, 'dessert': dessert}menu('chardonnay', 'chicken')- We can specify default values for parameters.

- If we provide an argument, it's used instead of the default:

def menu(wine, entree, dessert='pudding'): return {'wine': wine, 'entree': entree, 'dessert': dessert}menu('dunkelfelder', 'duck', 'doughnut')Functions

Specify Default Parameter Values

- The

buggy()function is expected to run each time with a fresh empty result list, add the arg argument to it, and then print a single-item list.

def buggy(arg, result=[]): result.append(arg) print(result)buggy('a')buggy('b') # expect ['b']- There's a bug: it's empty only the first time it's called.

- The second time, result still has one item from the previous call.

- It would have worked if it had been written like this:

def works(arg): result = [] result.append(arg) return resultworks('a')works('b')- The fix is to pass in something else to indicate the first call:

def nonbuggy(arg, result=None): if result is None: result = [] result.append(arg) print(result)nonbuggy('a')nonbuggy('b')Functions

Explode/Gather Positional Arguments with *

- When an asterisk (

*) is used inside the function with a parameter, it groups a variable number of positional arguments into a single tuple of parameter values.

def print_args(*args): print('Positional tuple:', args)print_args()print_args(3, 2, 1, 'wait!', 'uh...')- If our function has required positional arguments, as well, put them first;

*argsgoes at the end and grabs all the rest:

def print_more(required1, required2, *args): print('Need this one:', required1) print('Need this one too:', required2) print('All the rest:', args)print_more('cap', 'gloves', 'scarf', 'monocle', 'mustache wax')We can pass positional argument to a function, which will match them inside to positional parameters.

We can pass a tuple argument to a function, and inside it will be a tuple parameter.

We can pass positional arguments to a function, and gather them inside as the parameter

*args, which resolves to the tuple args.

- We can also "explode" a tuple argument called

argsto positional parameters*argsinside the function, which will be regathered inside into the tuple parameterargs:

def print_args(*args): print('Positional tuple:', args)print_args(2, 5, 7, 'x')args = (2,5,7,'x')print_args(args)print_args(*args)We can only use the

*syntax in a function call or definition.Outside the function,

*argsexplodes the tupleargsinto comma-separated positional parameters.Inside the function,

*argsgathers all of the positional arguments into a single args tuple.

Functions

Explode/Gather Positional Arguments with **

- We can use two asterisks (

**) to group keyword arguments into a dictionary, where the argument names are the keys, and their values are the corresponding dictionary values.

def print_kwargs(**kwargs): print('Keyword arguments:', kwargs)print_kwargs()print_kwargs(wine='merlot', entree='mutton', dessert='macaroon')- Inside the function,

kwargsis a dictionary parameter.

We can pass keyword arguments to a function, which will match them inside to keyword parameters.

We can pass a dictionary argument to a function, and inside it will be dictionary parameters.

We can pass one or more keyword arguments (name=value) to a function, and gather them inside as

**kwargs, which resolves to the dictionary parameter calledkwargs.Outside a function,

**kwargsexplodes a dictionarykwargsinto name=value arguments.Inside a function,

**kwargsgathers name=value arguments into the single dictionary parameterkwargs.

Functions

Keyword-Only Arguments

- a keyword-only argument is an argument that can only be provided as a keyword argument when a function is called.

- It is recommended to be provided as name=value.

def print_data(data, *, start=0, end=100): for value in (data[start:end]): print(value)- The single

*in the definition above means that the parametersstartandendmust be provided as named arguments if we don’t want their default values.

data = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']print_data(data)print_data(data, start=4)print_data(data, end=2)def print_data2(data, *, start, end): for value in data[start:end]: print(value)print_data2(data)print_data2(data, start=4)print_data2(data, end=2)print_data2(data, start = 2, end = 4)startandendare required arguments, because they doesn't have a default value and they must be specified as a keyword argument when we call theprint_data2()function.

Functions

Mutable and Immutable Arguments

Remember that if we assigned the same list to two variables, we could change it by using either one? And that we could not if the variables both referred to something like an integer or a string?

If an argument is mutable, its value can be changed from inside the function via its corresponding parameter.

outside = ['one', 'fine', 'day']def mangle(arg): arg[1] = 'terrible!'outsidemangle(outside)outsideExceptions

In some languages, errors are indicated by special function return values.

- Python uses exceptions: code that is executed when an associated error occurs.

When we run code that might fail under some circumstances, we also need appropriate exception handlers to intercept any potential errors.

- Accessing a list or tuple with an out-of-range position, or a dictionary with a nonexistent key.

- If we don’t provide your own exception handler, Python prints an error message and some information about where the error occurred and then terminates the program:

short_list = [1, 2, 3]position = 5short_list[position]Handle Errors with try and except

- Rather than leaving things to chance, use

tryto wrap your code, andexceptto provide the error handling:

short_list = [1, 2, 3]position = 5try: short_list[position]except: print('Need a position between 0 and', len(short_list)-1, ' but got', position)short_list = [1, 2, 3]position = 5try: short_list[position]except: print('Need a position between 0 and', len(short_list)-1, ' but got', position)- The code inside the

tryblock is run.- If there is an error, an exception is raised and the code inside the

exceptblock runs.

- If there is an error, an exception is raised and the code inside the

- If there are no errors, the

exceptblock is skipped.

Specifying a plain

exceptwith no arguments, as we did here, is a catchall for any exception type.If more than one type of exception could occur, it’s best to provide a separate exception handler for each.

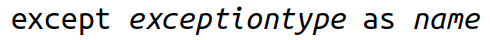

We get the full exception object in the variable name if we use the form:

short_list = [1, 2, 3]while True: value = input('Position [q to quit]? ') if value == 'q': break try: position = int(value) print(short_list[position]) except IndexError as err: print('Bad index:', position) except Exception as other: print('Something else broke:', other)- The example looks for an

IndexErrorfirst, because that’s the exception type raised when we provide an illegal position to a sequence. It saves an

IndexErrorexception in the variableerr, and any other exception in the variableother.The example prints everything stored in

otherto show what you get in that object.- Inputting position

3raised anIndexErroras expected. - Entering

twoannoyed theint()function, which we handled in our second, catchallexceptcode.

- Inputting position