Lecture 8

DANL 200: Introduction to Data Analytics

Byeong-Hak Choe

September 22, 2022

Announcement

Tutoring/TA-ing at Data Analytics Lab (South 321)

- Marcie Hogan (Tutor for DANL 100):

- Sunday, 2:00 PM--5:00 PM

- Wednesday, 12:30 PM--1:30 PM

- Andrew Mosbo (Tutor):

- Mondays, 4:00 PM--5:00 PM

- Wednesdays, 11:00 A.M.--noon

- Thursdays, 5:00 PM--6:00 PM

- Emine Morris (TA):

- Mondays and Wednesdays, 5:00 PM--6:30 PM

- Tuesdays and Thursdays, 3:00 PM--4:45 PM

Announcement

Homework Assignment 1

I have corrected typos in a web-version of Homework Assignment 1 (https://bcdanl.github.io/DANL200_hw1q.html), so that there should not be the same questions in the Homework.

In the starting R script, DANL200_hw1_q.R, I have not found critical typos yet.

- Let me know if you find any errors in homework.

Style of Coding and Commenting for Homework Assignment

##### Q2b. Provide both (1) `ggplot` codes and # (2) a couple of sentences# to describe the distribution of `cnt`.######### Answer for Q2b####ggplot(data = ... ) + geom_*(mapping = aes( ... )) # *** *** ***# The peak value ...# The distribution is .... skewed# Variable `cnt` is concentrated in an interval ...Style of Coding and Commenting for Homework Assignment

##### Q2g. Provide both (1) `ggplot` codes and # (2) a couple of sentences# to describe the relationship between `temp` and `cnt`.######### Answer for Q2g####ggplot(data = ... ) + geom_*(mapping = aes( ... )) # *** *** ***# `temp` is .... associated with ....# ....Workflow

Shortcuts for RStudio and RScript

Mac

- command + shift + N opens a new RScript.

- command + return runs a current line or selected lines.

- command + shift + C is the shortcut for # (commenting).

- option + - is the shortcut for

<-.

Windows

- Ctrl + Shift + N opens a new RS-cript.

- Ctrl + return runs a current line or selected lines.

- Ctrl + Shift + C is the shortcut for # (commenting).

- Alt + - is the shortcut for

<-.

Workflow

- Home/End moves the blinking cursor bar to the beginning/End of the line.

- Ctrl (command/fn for Mac Users) + / works too.

- PgUp/PgDn moves the blinking cursor bar to the top/bottom line of the script on the screen.

- Fn + / works too.

- Ctrl (command for Mac Users) + Z undoes the previous action.

- Ctrl (command for Mac Users) + Shift + Z redoes when undo is executed.

- Ctrl (command for Mac Users) + F is useful when finding a phrase (and replace the phrase) in the RScript.

- Ctrl (command for Mac Users) + D deletes a current line.

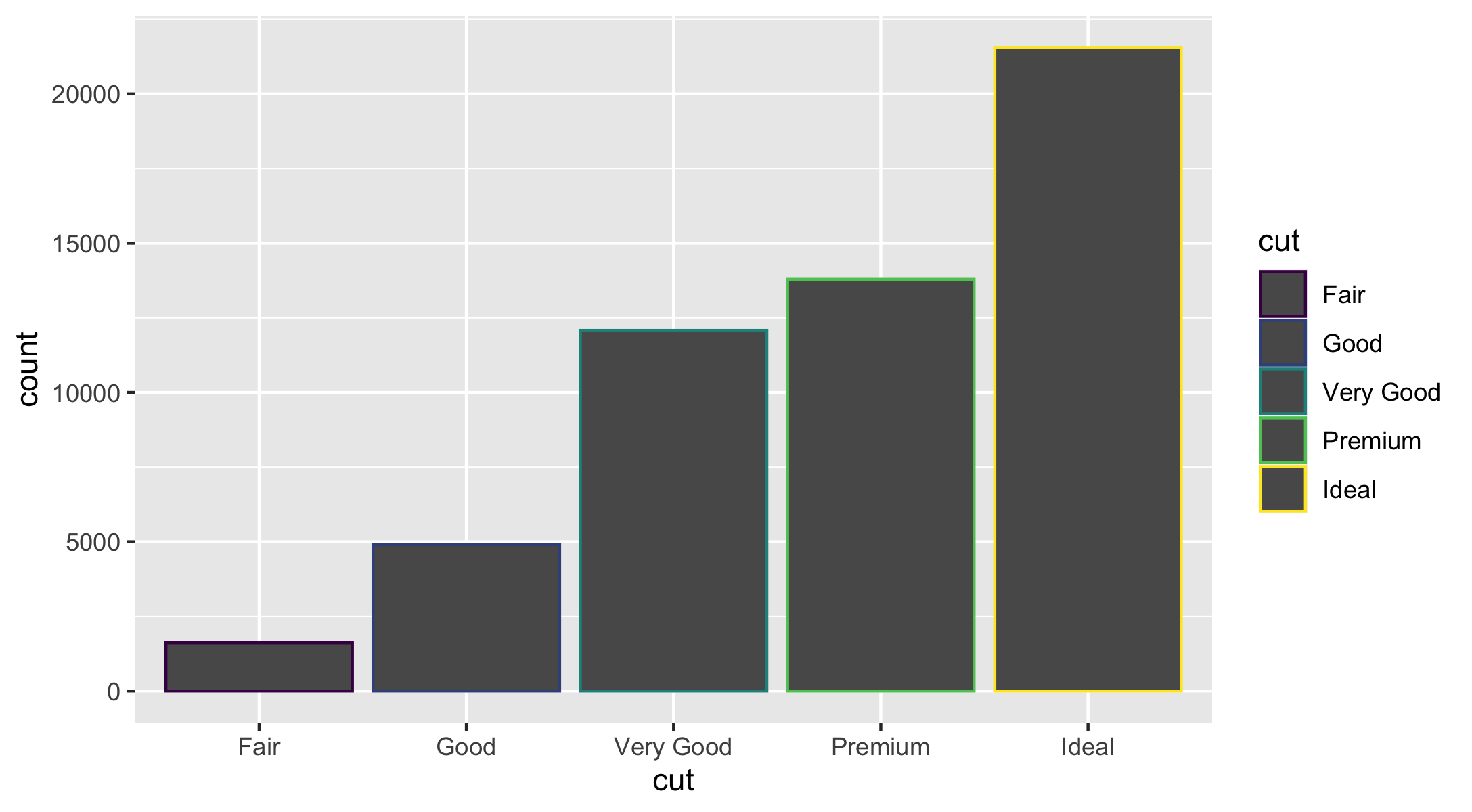

Statistical Transformation

Statistical Transformations

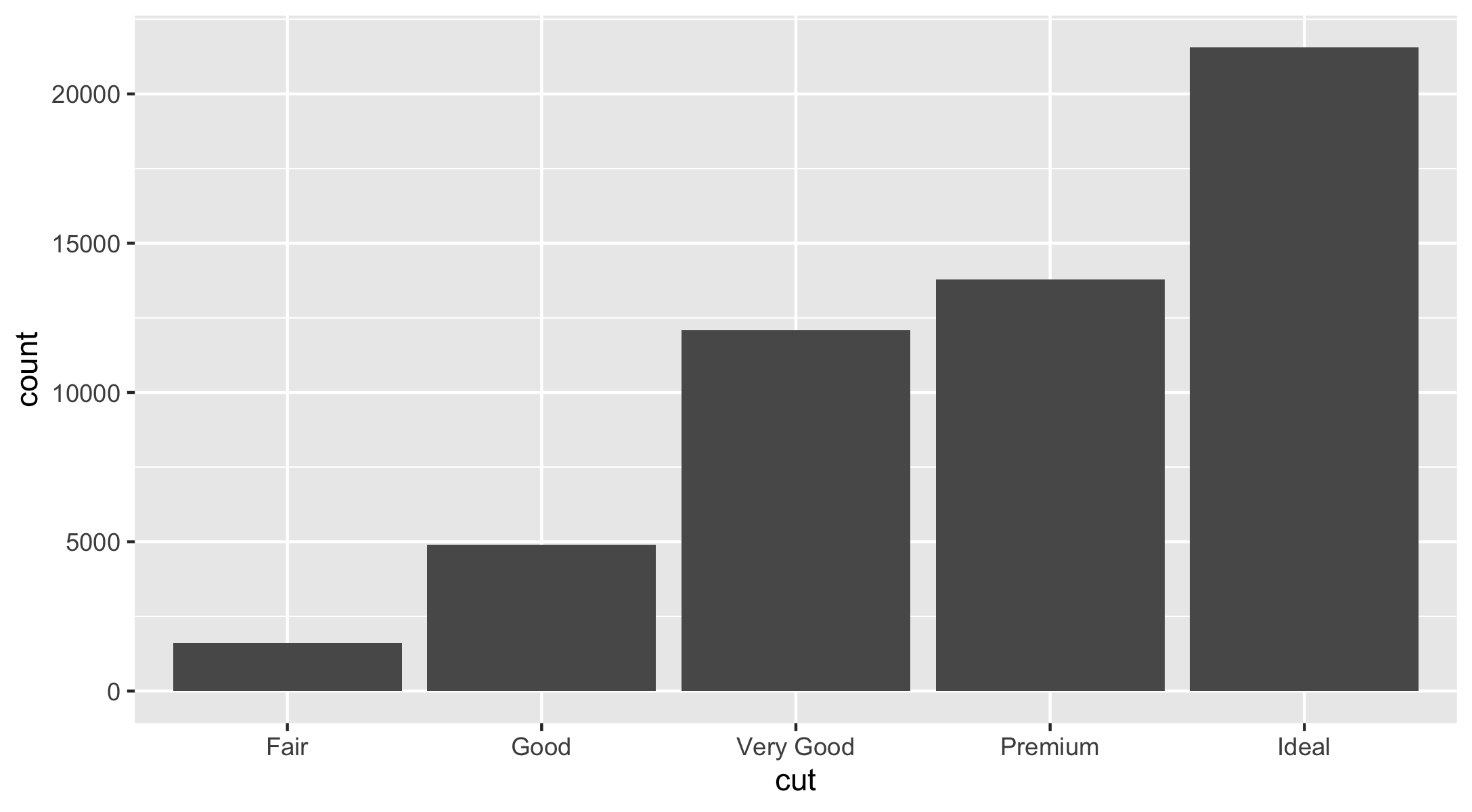

Bar charts seem simple, but they are interesting because they reveal something subtle about plots.

Consider a basic bar chart, as drawn with

geom_bar().The following bar chart displays the total number of diamonds in the

ggplot2::diamondsdataset, grouped bycut.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut))- The

diamondsdataset comes inggplot2and contains information about ~54,000 diamonds, including theprice,carat,color,clarity, andcutof each diamond.

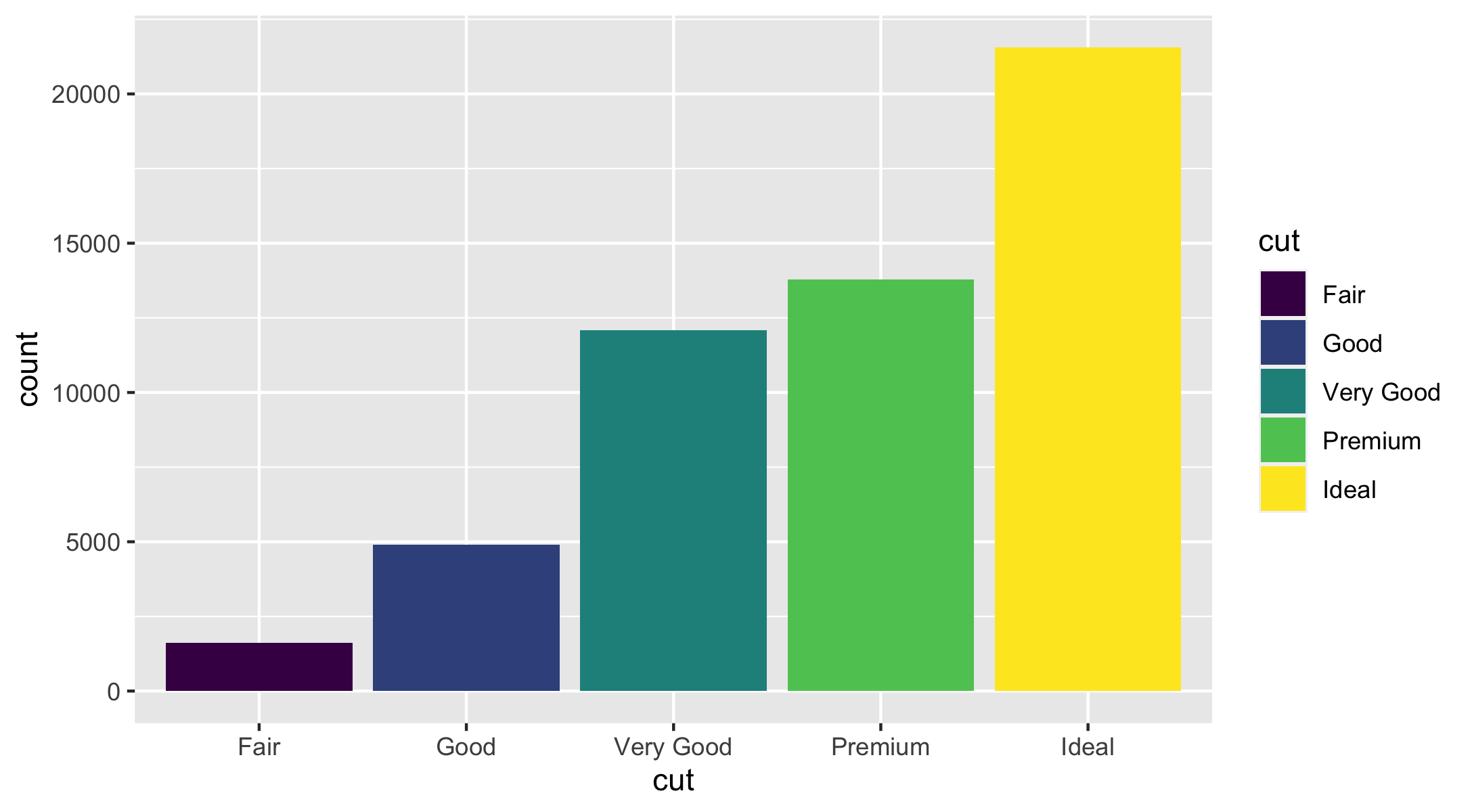

Statistical Transformations

The algorithm used to calculate new values for a graph is called a

stat, short for statistical transformation.The figure below describes how this process works with

geom_bar().

Statistical Transformations

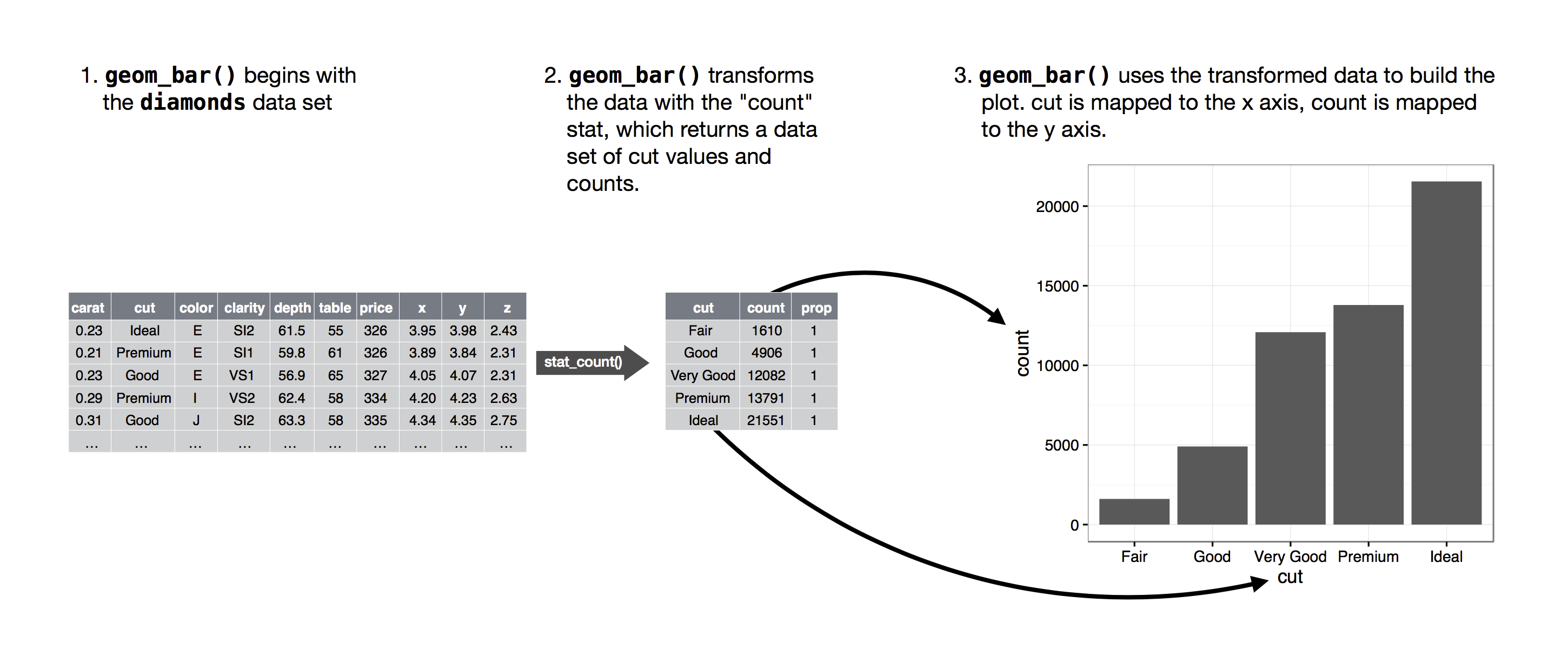

- Many graphs, including bar charts, calculate new values to plot:

, geom_histogram() and geom_freqpoly() bin your data and then plot bin counts, the number of observations that fall in each bin.

ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = hwy)) + geom_histogram(binwidth = 1, fill = NA, color = "blue") + geom_freqpoly(binwidth = 1, color = "red")

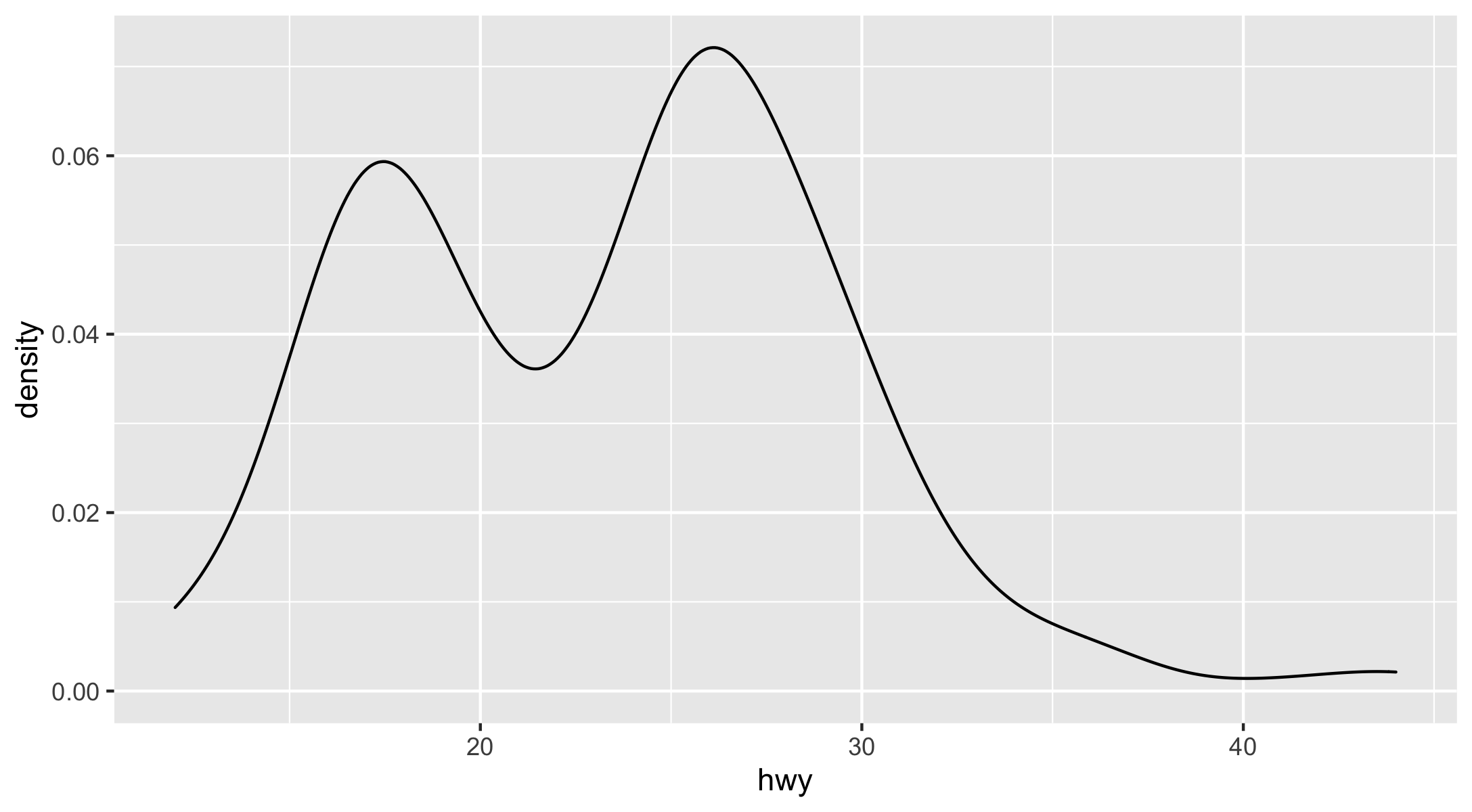

geom_density()plots a probability density function.- The area under the density plot is re-scaled to equal one.

- We can think of a density plot as a continuous histogram of a variable.ggplot(data = mpg,mapping =aes(x = hwy)) +geom_density()

geom_bar() is a histogram for discrete data.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut))

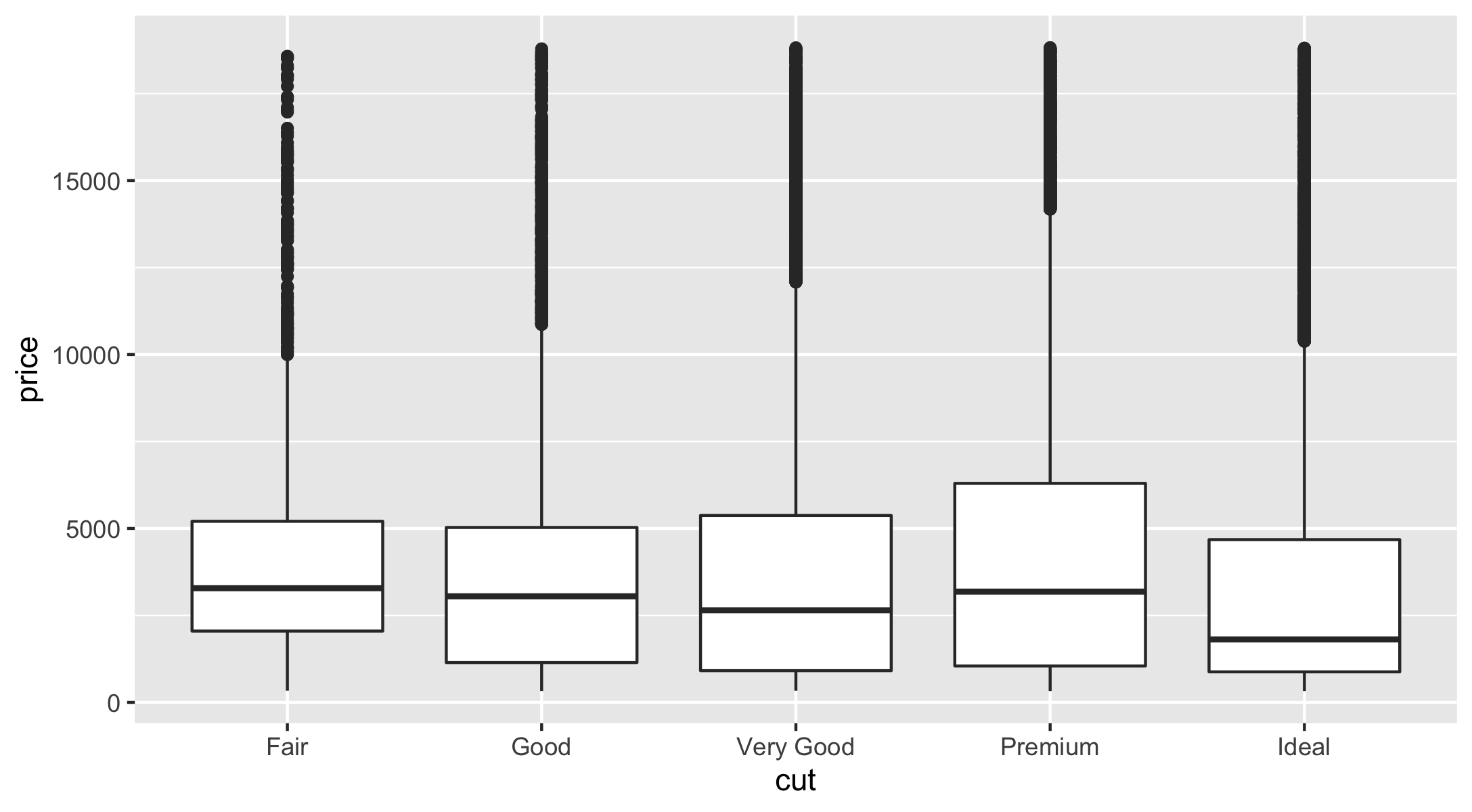

geom_boxplot()compute a summary of the distribution and then display a specially formatted box.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_boxplot(mapping = aes(x = cut, y = price))

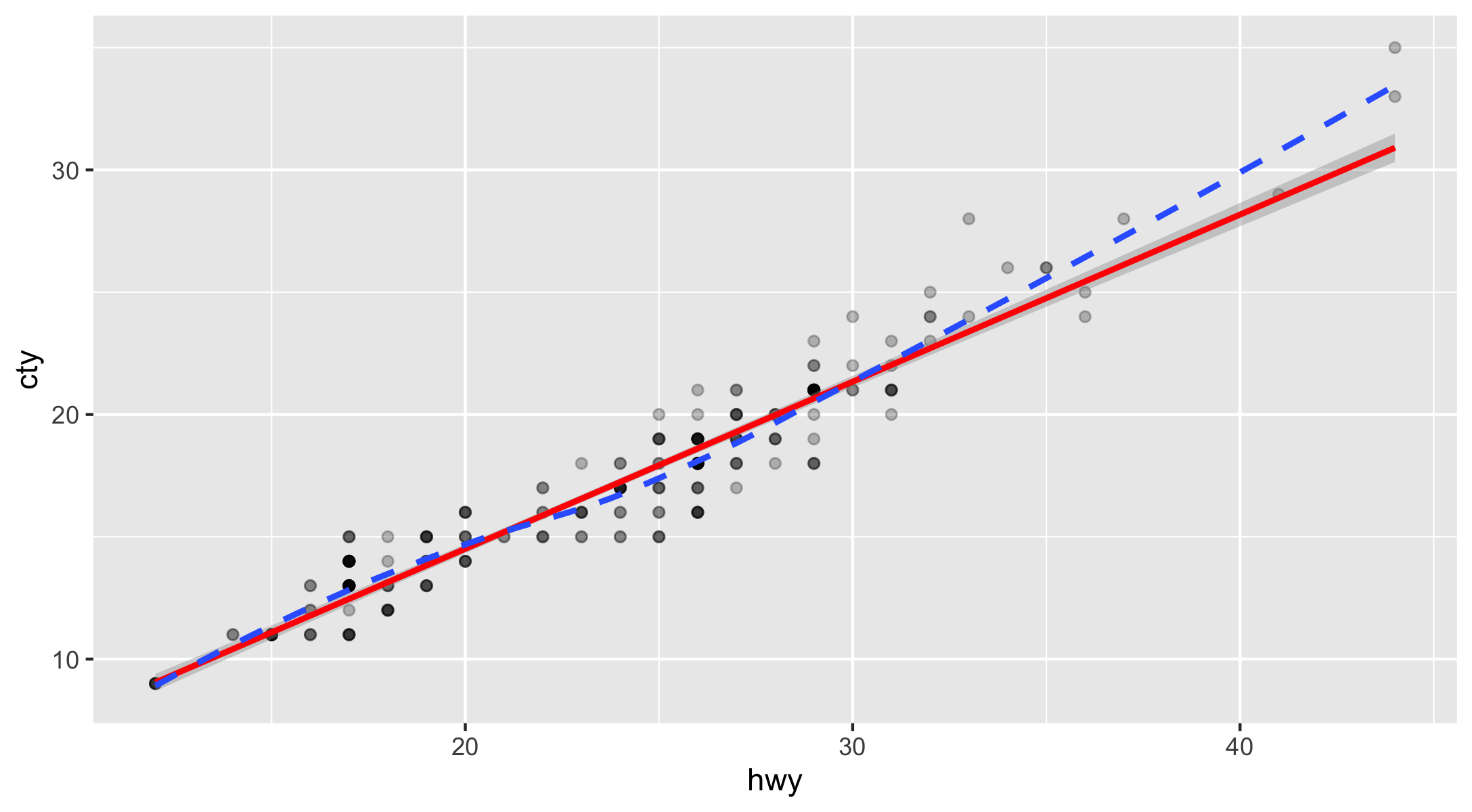

geom_smooth()fits a model to your data and then plot predicted values ofyfrom the model.

ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = hwy, y = cty)) + geom_point(alpha = .25) + geom_smooth(method = lm, color = 'red') + geom_smooth(linetype = 2, se = FALSE)

Statistical Transformations

Observed Value vs. Number of Observations

There are three reasons we might need to use a

statexplicitly:- 1. We might want to override the default

stat.

- 1. We might want to override the default

demo <- tribble( # for a simple data.frame ~cut, ~freq, "Fair", 1610, "Good", 4906, "Very Good", 12082, "Premium", 13791, "Ideal", 21551 )ggplot(data = demo) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, y = freq), stat = "identity")Statistical Transformations

Count vs. Proportion

There are three reasons we might need to use a

statexplicitly:- 2. We might want to override the default mapping from transformed variables to aesthetics.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, y = after_stat(prop), group = 1))Statistical Transformations

Stat summary

There are three reasons we might need to use a

statexplicitly:- 3. We might want to draw greater attention to the statistical transformation in our code.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + stat_summary( mapping = aes(x = cut, y = depth), fun = median, fun.min = min, fun.max = max )Statistical Transformations

Exercises

What is the default geom associated with

stat_summary()? How could you rewrite the previous plot to use that geom function instead of the stat function?What does

geom_col()do? How is it different togeom_bar()?Most

geomsandstatscome in pairs that are almost always used in concert. Read through the documentation and make a list of all the pairs. What do they have in common?What variables does

stat_smooth()compute? What parameters control its behavior?

Statistical Transformations

Exercises

- In our proportion bar chart, we need to set

group = 1. Why? In other words what is the problem with these two graphs?

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, y = stat(prop) ) )ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, y = stat(prop), fill = color ) )Position Adjustment

Position Adjustments

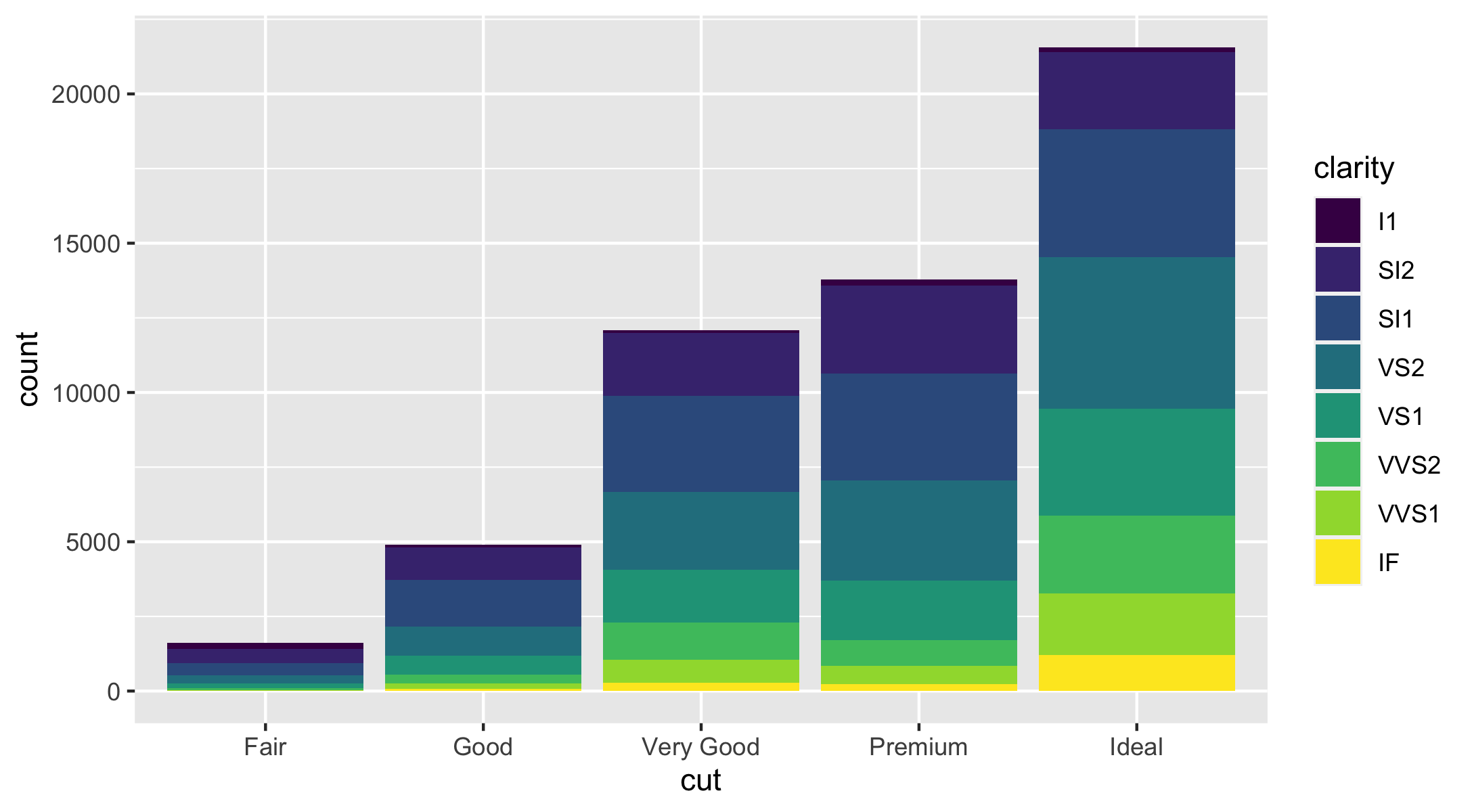

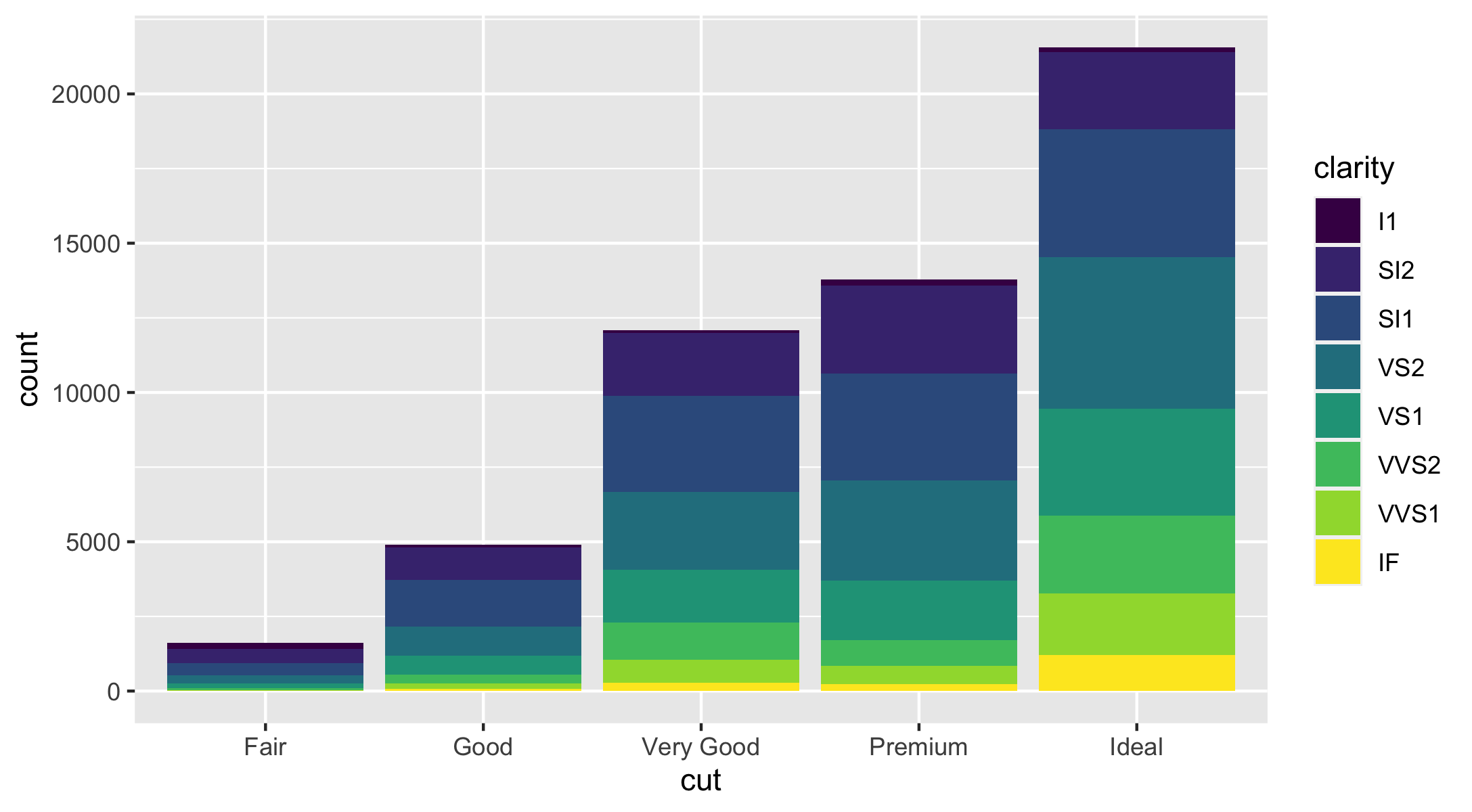

Stacked bar charts with fill aesthetic

- Note that the bars are automatically stacked if we map the

fillaesthetic to another variable.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, fill = clarity) )

Position Adjustments

Stacked bar charts with fill aesthetic

- The

stacking is performed automatically by the position adjustment specified by thepositionargument.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, fill = clarity), position = "stack")

Position Adjustments

position = "fill" and position = "dodge"

- If we don't want a stacked bar chart with counts, we can use one of two other

positionoptions:fillordodge.

position = "fill"works like stacking, but makes each set of stacked bars the same height.- This makes it easier to compare proportions across groups.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, fill = clarity), position = [?])position = "dodge"places overlapping objects directly beside one another.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = cut, fill = clarity), position = [?])Position Adjustments

Overplotting and position = "jitter"

The values of

hwyanddisplare rounded so the points appear on a grid and many points overlap each other.- This problem is known as overplotting.

We can avoid the overlapping problem by setting the position adjustment to

jitter.position = "jitter"adds a small amount of random noise to each point.

ggplot(data = mpg) + geom_point(mapping = aes(x = displ, y = hwy), position = [?])Position Adjustments

Exercises

- What is the problem with this plot? How could you improve it?

ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = cty, y = hwy)) + geom_point()What parameters to

geom_jitter()control the amount of jittering?Compare and contrast

geom_jitter()withgeom_count().What’s the default position adjustment for

geom_boxplot()? Create a visualization of thempgdataset that demonstrates it.

Coordinate

Coordinate Systems

The default coordinate system is the Cartesian coordinate system where the

xandypositions act independently to determine the location of each point.There are a number of other coordinate systems that are occasionally helpful.

Coordinate Systems

coord_flip()

coord_flip()switches thexandyaxes.This is useful (for example), if we want horizontal boxplots.

It's also useful for long labels: it's hard to get them to fit without overlapping on the

x-axis.

ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = class, y = hwy)) + geom_boxplot()ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = class, y = hwy)) + geom_boxplot() + coord_flip()Coordinate Systems

coord_quickmap()

coord_quickmap()sets the aspect ratio correctly for maps.

county <- map_data("county") # Map data for US Countiesny <- filter(county, # We will discuss 'filter()' in the next chapter region == "new york")ggplot(ny, aes(long, lat, group = group)) + geom_polygon(fill = "white", color = "black")ggplot(ny, aes(long, lat, group = group)) + geom_polygon(fill = "white", color = "black") + coord_quickmap()Coordinate Systems

Exercises

What does

labs()do? Read the documentation.What does the plot below tell you about the relationship between city and highway mpg? Why is

coord_fixed()important? What doesgeom_abline()do?

ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = cty, y = hwy)) + geom_point() + geom_abline() + coord_fixed()ggplot Grammar

The Layered Grammar of Graphics

- Let's add position adjustments, stats, coordinate systems, and faceting to our code template.

ggplot(data = <DATA>) + <GEOM_FUNCTION>( mapping = aes(<MAPPINGS>), stat = <STAT>, position = <POSITION>) + <COORDINATE_FUNCTION> + <FACET_FUNCTION>- The seven parameters---(1) a dataset, (2) a geom, (3) a set of mappings, (4) a stat, (5) a position adjustment, (6) a coordinate system, and (7) a faceting scheme---in the template compose the grammar of graphics, a formal system for building plots.

Exploraty Data Analysis I

Exploraty Data Analysis

Get to know data before modeling

- We need to explore the data before building the model.

- No dataset is perfect.

- We'll have a more specific idea of what information most accurately predicts the outcome.

- Data exploration uses a combination of ...

- Summary statistics

- Visualization

- Data transformation

Exploraty Data Analysis

Example

Suppose your goal is to build a model to predict which of our customers don't have health insurance.

We've collected a dataset of customers whose health insurance status you know.

We've also identified some customer properties that you believe help predict the probability of insurance coverage:

- age

- employment status

- income

- information about residence and vehicles, and so on

Summary Statistics

Summary Statistics

- Use the

summary()orskimr::skim()command to take your first look at the data.- They report a variety of summary statistics on the numerical variables of the data frame, and count statistics on any categorical variables.

library(tidyverse)library(skimr)path <- "PATH_NAME_FOR_THE_FILE_custdata.RDS"customer_data <- readRDS(path)# The following is the same data file in my website.path_web <- "https://bcdanl.github.io/data/custdata.csv"customer_data <- read.table(path_web, sep = ',', header = TRUE)skim(customer_data)Summary Statistics

Typical problems revealed by data summaries

At this stage, we're looking for several common issues:

- Missing values

- Invalid values and outliers

- Data ranges that are too wide or too narrow

- The units of the data

Generally, the goal of modeling is to make good predictions on typical cases, or to identify causal relationships.

A model that is highly skewed to predict a rare case correctly may not always be the best model overall.

Summary Statistics

Missing values

The variable

is_employedis missing for more than a third of the data.- Why?

## is_employed## FALSE: 2321## TRUE :44887## NA's :24333Summary Statistics

Data range and variation

We should pay attention to how much the values in the data vary.

- Outliers are data points that fall well out of the range of where you expect the data to be.

skim(customer_data$income)skim(customer_data$age)Summary Statistics

Units

- We may not know that variable

IncomeKis defined as

IncomeK=customer_data$income/1000.

- Looking only at the summary, the values could plausibly be interpreted to mean either "hourly wage" or "yearly income in units of $1,000."

IncomeK <- customer_data$income/1000skim(IncomeK)- This is actually something that we’ll catch by checking data definitions in data dictionaries or documentation, rather than in the summary statistics.

Visualization

Key Points in Visualization

A graphic should display as much information as it can, with the lowest possible cognitive strain to the viewer.

Strive for clarity. Make the data stand out. Specific tips for increasing clarity include these:

- Avoid too many superimposed elements, such as too many curves in the same graphing space.

- Find the right aspect ratio and scaling to properly bring out the details of the data.

- Avoid having the data all skewed to one side or the other of your graph.

Visualization is an iterative process. Its purpose is to answer questions about the data.

Visualization

Visually checking distributions for a single variable

- We will look at histograms, density plots, bar charts, and dot plots.

The above visualizations help us answer questions like these:

What is the peak value of the distribution?

How many peaks are there in the distribution (unimodality versus bimodality)?

How normal is the data?

How much does the data vary? Is it concentrated in a certain interval or in a certain category?

Visualization

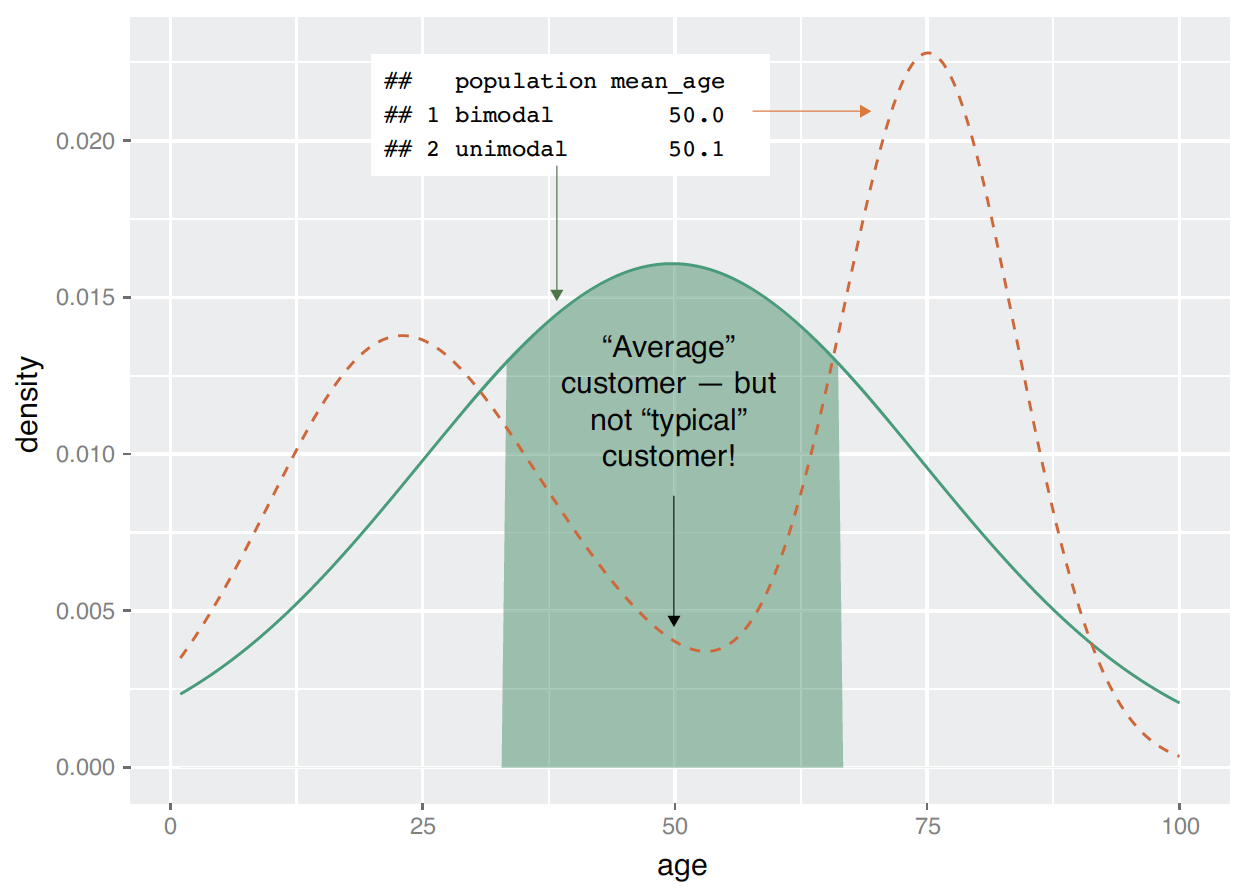

Visually checking distributions for a single variable

- One of the things that’s easy to grasp visually is the shape of the distribution of variable.

ggplot(data = customer_data) + geom_density( mapping = aes(x = age) )- The graph here is somewhat flattish between the ages of about 25 and about 60, falling off slowly after 60.

- There seems to be a peak at around the late-20s to early 30s range, and another in the early 50s.

- This data has multiple peaks: it is not unimodal.

- Distribution peaks around mid/late 20s. Peaks again in early 50s.

Visualization

Visually checking distributions for a single variable

Visualization

Histograms

A basic histogram bins a variable into fixed-width buckets and returns the number of data points that fall into each bucket as a height.

A histogram tells you where your data is concentrated. It also visually highlights outliers and anomalies.

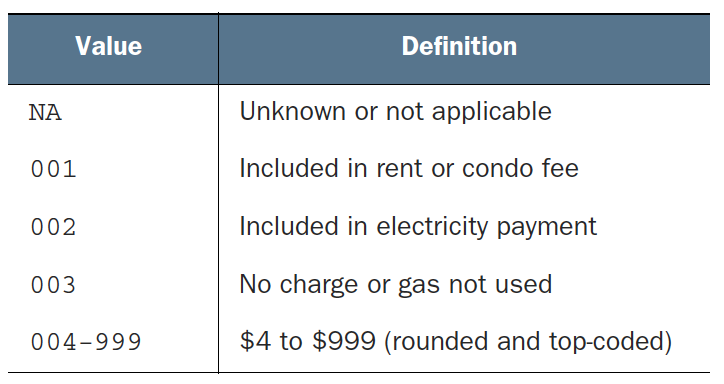

ggplot( data = customer_data, aes(x=gas_usage) ) + geom_histogram( binwidth=10, fill="gray" )skim(customer_data$gas_usage)Visualization

Data dictionary entry for gas_usage

- Treat values

001,002, and003as numerical values could potentially lead to incorrect conclusions in our analysis.

Visualization

Density plots

We can think of a density plot as a continuous histogram of a variable.

- The area under the density plot is re-scaled to equal one.

- We can think of a density plot as a continuous histogram of a variable.

library(scales) # to denote the dollar sign in axesggplot(customer_data, aes(x=income)) + geom_density() + scale_x_continuous(labels=dollar)Visualization

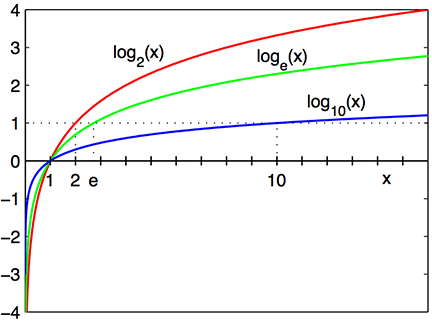

A Little Bit of Math for Logarithm

- The logarithm function, y=logb(x), looks like ....

log10(100): the base 10 logarithm of 100 is 2, because 102=100

loge(x): the base e logarithm is called the natural log, where $e = 2.718\cdots$'' is the mathematical constant, the Euler's number.

log(x) or ln(x): the natural log of x .

loge(7.389⋯): the natural log of 7.389⋯ is 2, because e2=7.389⋯.

Visualization

Log Transformation

We should use a logarithmic scale when percent change, or change in orders of magnitude, is more important than changes in absolute units.

A difference in income of $5,000 means something very different across people with different income levels.

- We should also consider using a log scale to reduce a variance of residuals when a variable is heavily skewed.

Visualization

Log Transformation

- The log transformation makes the skewed distribution of income more normal.

ggplot(customer_data, aes(x=income)) + geom_density() + scale_x_log10(breaks = c(10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000), labels=dollar)Visualization

Bar Charts and Dotplots

- A bar chart is a histogram for discrete data.

- It records the frequency of every value of a categorical variable.

ggplot( data = customer_data, mapping = aes( x = marital_status ) ) + geom_bar( fill="gray" )Visualization

Bar Charts and Dotplots

- Bar charts are most useful when the number of possible values is fairly large, like state of residents.

ggplot(customer_data, aes(x=state_of_res)) + geom_bar(fill="gray") + coord_flip()- A horizontal bar chart can be easier to read when there are several categories with long names.

Visualization

Bar Charts and Dotplots

- Sometimes it is better to sort the data when plotting a bar chart or dot plot.

library(WVPlots) # install.package("WVPlots") if you have notClevelandDotPlot(customer_data, "state_of_res", sort = 1, title="Customers by state") + coord_flip()- Sorted bar chart or dot plot can allow use to extract insight more efficiently from the data.

Visualization

Visually checking relationships between two variables

We'll often want to look at the relationship between two variables.

Is there a relationship between the two inputs---age and income---in my data?

If so, what kind of relationship, and how strong?

Is there a relationship between the input, marital status, and the output, health insurance? How strong?

Visualization

A relationship between age and income

- Reasonable age and income values can be selected.

- We'll discuss the

filter()function soon.

- We'll discuss the

customer_data2 <- filter(customer_data, 0 < age & age < 100 & 0 < income & income < 200000)cor(customer_data$age, customer_data$income)Visualization

A relationship between age and income

ggplot( data = customer_data2 ) + geom_smooth( mapping = aes(x = age, y = income) )ggplot(customer_data2, aes(x=age, y=income)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth() + ggtitle("Income as a function of age")library(hexbin) # install.packages("hexbin) if you have not.ggplot(customer_data2, aes(x=age, y=income)) + geom_hex() + geom_smooth(color = "red", se = F) + ggtitle("Income as a function of age")Visualization

A relationship between marital status and health insurance

- Bar charts can be used to describe a relationship between two categorical variables.

ggplot(customer_data, aes(x=marital_status, fill=health_ins)) + geom_bar()# side-by-side bar chartggplot(customer_data, aes(x=marital_status, fill=health_ins)) + geom_bar([?])# stacked bar chartggplot(customer_data, aes(x=marital_status, fill=health_ins)) + geom_bar([?])Visualization

The Distribution of Marriage Status across Housing Types

cdata <- filter(customer_data, !is.na(housing_type))ggplot(cdata, aes(x=housing_type, fill=marital_status)) + geom_bar(position = "dodge") + scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Dark2") + coord_flip()ggplot(cdata, aes(x=marital_status)) + geom_bar(fill="darkgray") + facet_wrap(~housing_type, scale="free_x") + coord_flip()Visualization

Visually checking relationships between two variables

Overlaying, faceting, and several aesthetics should always be considered with the following geometric objects:

- Scatter plot

- Smoothing curve

- Bar chart

- Stacked bar chart

- Side-by-side bar chart

- Density plot

- Histogram

- Frequency ploygon

- Hexbin plot